Emily Bremer became captivated by constitutional law when she was a sophomore in college. At that point, she knew she wanted to become a law professor. In her mind, she would go to law school and then head straight to academia. She planned never to practice law, particularly in a large law firm or for the federal government.

She ended up doing both. Each provided a stepping stone to her ultimate goal of becoming a professor. Bremer spent three years at the University of Wyoming College of Law before coming to Notre Dame Law School as an associate professor in 2018.

Bremer knew early on that she wanted to come to Notre Dame Law School. She was attracted by its strong reputation for scholarship and teaching, as well as its commitment to its Catholic character and mission. Perhaps because of that mission, Bremer finds the Law School to be very family friendly and supportive.

“It is natural for your professional and personal lives to interact,” said Bremer. “Your personal commitments will affect your professional life, and it is a joy to be part of an institution that supports and embraces the whole person.”

Bremer has emerged as a leading expert and scholar in the area of administrative law. She looks specifically at the cross-cutting rules and procedures that federal agencies are required to follow when administering the law, such as by determining Social Security benefits, licensing telecommunications companies, enforcing immigration laws or deciding how other laws apply to individual cases.

After clerking for a federal judge and practicing law in the telecommunications and appellate group of a Washington, D.C., law firm, she went to work for the Administrative Conference of the United States, an independent agency that studies administrative procedure and makes recommendations for improvements to federal agencies, the president and Congress.

Working at the Administrative Conference provided opportunities to write and publish research, helping Bremer work toward her goal of becoming a professor. She took on several in-house research projects, one of which sparked her interest in why the procedures used in administrative adjudication are so highly variable across agencies.

“There is an expectation that similar agencies of the government will operate similarly. It can be really challenging for ordinary citizens who appear before agencies to understand the process and know what to expect when every agency uses unique procedures,” she said.

She pointed out that the administrative process should be transparent so that people can tell whether the government is keeping the promises that Congress makes when it passes laws and creates agencies to administer those laws.

“Uniformity and transparency in the administrative process are essential for there to be public trust in agencies. And for the system to work well,” said Bremer, adding that agencies do the best they can with limited resources.

“That is why good, thoughtful, across-the-board reform is important. Agencies should not have to reinvent the wheel, and it is inefficient and unhelpful to deprive them of a workable legal framework,” said Bremer.

“That is why good, thoughtful, across-the-board reform is important. Agencies should not have to reinvent the wheel, and it is inefficient and unhelpful to deprive them of a workable legal framework.”

Recently, she has been doing historical research on what is considered administrative law’s most important framework — the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 (APA). The APA governs the procedures that all federal agencies use to develop rules or resolve individual cases.

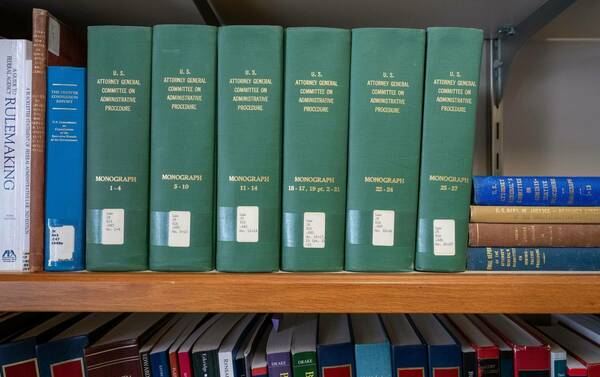

Many scholars have read the APA’s legislative history, but not many can say they have read the nearly 1,400 pages of research that supplied the law’s intellectual foundation. Bremer spent her pandemic summer of 2020 doing just that. From that research came her paper, “The Rediscovered Stages of Agency Adjudication,” which was published last year in the Washington University Law Review. She received the 2023 Emerging Scholar Award from the American Association of Law Schools Section on Administrative Law for her article.

Bremer brings to light a forgotten understanding of the distinction between informal and formal adjudication in the APA. These are not two different modes of adjudication but are rather consecutive stages in the adjudicative process.

“Somewhere along the way we forgot that adjudication is a staged process in which the hearing comes last and is always, by definition, formal. We started to think of it more like rulemaking, which can include either an informal or a formal hearing,” said Bremer.

The research clarifies the APA’s meaning and intent, calling upon courts and scholars to rethink the modern approach to interpreting and applying the APA’s formal hearing requirements. She says hundreds of agencies are conducting adjudicatory hearings, but they are not conducting them under the APA. Bremer believes this is a problem in need of a solution that is workable for agencies, ensures due process of law and has broad political support.

In addition to her work on adjudication, Bremer recently published an article in the Cornell Law Review that uncovers the administrative practices that inspired the APA’s attempt to inject democracy into the administrative rulemaking process.

In 2021, Bremer collaborated with Kathryn Kovacs, a law professor at Rutgers Law School who also writes about the history of the APA, and Charlotte Schneider, the head of public services at Rutgers Law Library. Together they developed the Bremer-Kovacs Collection: Historic Documents Related to the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946, a comprehensive database designed to make the APA’s history more accessible to researchers and practitioners. The Bremer-Kovacs Collection is available on HeinOnline.

For this work, the trio won the 2022 Joseph L. Andrews Legal Literature Award from the American Association of Law Libraries. They hope the collection will expand as additional archival research on the APA is undertaken.

At Notre Dame Law School, Bremer teaches first-year law students their required civil procedure course and also teaches administrative law, an upper-level elective course. Bremer brings unbounded enthusiasm to these notoriously difficult and dry subjects. She jokes to her students, “You can always rest assured that at least one of us is having fun.”

“Most law and policy is made and enforced through agencies. Studying administrative law is a crucial component of legal education,” she said.

She finds her students to be wonderful, intellectually curious people and is always thrilled to talk with them about their career plans. She views her role as educating them, helping them chart their path, and encouraging them to think long-term about how they want to contribute to society as a lawyer.

“They are all different people, with a variety of backgrounds and aspirations. Whatever they want to do, I view my job as helping them get there. I am happy to give them all the support and advice I can,” said Bremer.

Bremer says one of her own greatest gifts was her dad’s encouragement, as well as the belief he instilled in her that she could do whatever she wanted if she put in the work. “He said, ‘People will say you can’t do certain things because you are a girl, but that is wrong, ignore them,’” she said.

“I felt called to be an academic. It took many years longer than I thought it would, but I kept plugging away, writing and publishing. And eventually it happened,” said Bremer. “I am really grateful that my dad gave me that deeply ingrained belief that if I just kept working I could do it. In the end, I did.”

She tells her students the same thing her dad told her. She also tells them that a big part of establishing a legal career is getting rejected. “There is much more failure than success, and we make that reality invisible. No career is a straight shot. I tell them never to take themselves out of the running for a good opportunity. You will get a lot of ‘nos.’”

“But,” Bremer adds, “you will get the ‘yeses’ you are supposed to get.”